On True Belief, False Mysticism, and Reading the Cosmos

Part IV: The Symbolic and the Archetypal

This excerpt, attributed to the newly resurrected Christ, appears on the official website of the Maria Valtorta Heritage Foundation:

And I go out into the garden full of flower buds and of dew. And the apple-trees open their corollas to form a flowery arch over My Royal head and the grass makes a carpet of gems and corollas for My Foot, that treads again on the Earth redeemed after being lifted up on it to redeem it. And the early sun, and the sweet April wind, and the light cloud that passes by, as rosy as the cheek of a child, and the birds among branches, they all greet Me.

Note the contrast to the ancient homily in the Office of Readings, where Christ enters “bearing the cross, the weapon that had won him the victory. At the sight of him Adam… struck his breast in terror”. Clearly, having just harrowed Hell and risen again on the third day, our blessed Lord would be given over to flights of unrestrained Victorian orotundity, while promenading about through the scenery.

Valtorta’s writings, 16,420 original manuscript pages, are similarly ornate throughout. I tried to engage with them seriously as a teenager at the behest of a pious older woman, who spoke of them as “food and sustenance.” I had absolutely no idea what I was getting into. I have not looked at them since. A lengthy description of the appearance of a crow somehow remains in my memory. Jesus is bar mitzvahed. He does carpentry work, with a screwdriver.

The mystic who grows roses – no, she is not a floriculturist – attributes these words to the Virgin Mary (original punctuation retained):

Daughter, children, the fruits of this day are sanctifying graces for your souls... they are of supernatural life of better days, in the steep mountain you are climbing..! My rays which come from the sun of justice of My Divine Son will dazzle you. Be loyal to His Doctrine..! Lead an evangelical, secular and apostolic life..! And appraise the faith, love and unity of the blessed ones..! Now look at the resplendent sun behind the billowing clouds of cotton, and the fine divine rain.

Even the heaviest storms do not seem to dampen the periphrastic reportage of these mystics:

The raging wind was now of a hurricane nature. The sky was inky black, without stars. Thick, black, hanging clouds could be seen through lightning flashes as if they were falling and sprawling in unbelievable phantasmal designs across the lake and shore. Suddenly they were pushed and whipped high into the air, and thin spray like frozen fringe cut across the faces of the Master and Simon.

We owe this passage to the currently fêted American visionary, Cora Evans.

Confounding spirituality with grandiloquence (which involves poor command of language and logic, both of which one would expect to find supereminently present with the Divine Word) seems to be a particular trap. Not that any of these mystic writers are without native flair, but raw gift remains utterly undisciplined and untrained; certainly, they exhibit no writer’s block, which is remarkable in itself.

Author Sandra Miesel conveys that “Valtorta is supposed to have offered God the sacrifice of her intelligence in 1949. She gradually ceased writing as mental aberrations increased over the next decade. By the time of her death in 1961, she had reached what Fr. Benedict Groeschel, C.F.R. [a professor of psychology] has described as ‘a state similar to catatonic schizophrenia’.” As a community member quipped in the comments beneath Miesel’s article, “What could possibly go wrong?” Back to the question of style, however; Miesel notes that the problems of florid prose are often exacerbated in translation: “a line of laden donkeys is rendered as an ‘asinine cavalcade’.”

In Leisure, the Basis of Culture, Josef Pieper states unequivocally that the suppression of religion, philosophy and the arts is a far lesser evil than “the distortion into false forms of the original.” The spiritual decoys which arise from this distortion divert one from the path, confuse the mind, and damage the psyche. “[T]here are such pseudo-realizations of those basic experiences, which only appear to pierce the canopy. There is a way to pray, in which ‘this’ world is not transcended, in which, instead, one attempts to incorporate the divine as a functioning component of the work-a-day machinery of purposes.” The affinity between the fanciful and the utilitarian may not be evident at first glance, yet consider how invariably such narratives transition into prejudice, programs and politics; much could be said as to why this follows, by a certain necessity, on their own inner logic. “Religion,” Pieper tells us, “can be perverted into magic so that instead of self-dedication to God, it becomes an attempt to gain power over the divine and make it subservient to one’s own will,” and this we have been examining at length; “prayer can be a technique for continuing to live life ‘under the canopy’.”

Now we must look more closely at why and how this is so. In his razor-sharp essay, “Absurdity in Sacred Decoration” (the title alone of which does much to convey the content, for its unapologetic admission that there is such a thing), Thomas Merton, writing as a Trappist father, recounts a ciborium in a tabernacle overlayed by a veil on which was depicted... a chalice and host. Although Fr. Louis didn’t put it quite this way (although in the present day he might well have, given the tenor of the piece), we see here something like Ikea assembly instructions, ensuring efficient function despite the consumer’s deficits of reading comprehension and/or of common sense. For Merton there is no dispute that “liturgical symbol is a vital and effective force in the life of prayer – it plays an active part in our worship.” Yet “mere decoration is inert, confusing, and a kind of dead-weight on prayer. It distracts not in the superficial sense of substituting one concept for another, but in a deeper way: by drawing us from the realm of intuition and of mystery into the more superficial level of sentimental fantasy.”

“Symbolic objects,” Merton tells us, “are effective by their own actuality, their concrete presence and function.” In contrast, the useless proliferation of images, born of a carnal mind, substitutes for the invisible. It is, in Pieper’s words, “painting decorations on the interior surface of the dome.” It is anti-contemplative.

Literal-minded prolixity is antithetical to the authentically mystical. In the Spiritual Canticle, the exchange of the soul and her Beloved set as sublime eclogues, St. John of the Cross treats of the inadequacy unto failure of all linguistic and imaginative concepts: “Who can describe in writing the understanding he [the Beloved] gives to loving souls in whom he dwells? And who can express with words the experience he imparts to them? Who, finally, can explain the desires he gives them? Certainly, no one can! Not even they who receive these communications!”

All who are free, tell me a thousand graceful things of you; all wound me more and leave me dying of, ah, I-don't-know-what behind their stammering.

The translation of Frs. Kieran Kavanaugh and Otilio Rodriguez, O.C.D. is masterful, high art and theology in its own right, however ancillary in nature. One need only compare and contrast to see verified: the letter brings death, but the spirit gives life.

Fr. Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, O.P. explains that, as regards spiritual matters, the influence of temperament and natural dispositions inclines us “to note only [the] material elements which adapt themselves better to our tastes, and to lose sight of the spirit which determines their nature and is the soul of the doctrinal body... Following this way, under pretext of reliance on what is tangible, mechanically exact, and incontestably certain even for the incredulous, we would end by explaining the higher by the lower, by reducing the first to the second, which is the very essence of materialism in all its forms.” Returning to Merton, we see that the road to materialism is paved with pious sentiments: “No amount of subjective sincerity can completely offset the corrupting effect of vulgarity and materialism in prayer.” And were that not enough, “[n]eedless to say, when the decoration itself is in bad taste, the results are even worse.” What are the results? – let us heed Lagrange: “we would rapidly dwarf everything and, instead of living supernaturally according to the true sense of this word, we might, despite certain appearances, flounder about in what is mediocre and mean.”

To the objection that the rubrics require a crucifix for the celebration of Mass, Merton is astute to point out that the cross is “an eschatological sign of Christ's victory over sin and death.” He opposes this to “magic lantern slides” and “graphic representations” of Christ, cringeworthy and out of place. Just as a pictorial labeling of the elements of liturgy darkens their transparency to mystery – reducing them by way of facile categorization – multiplying words ad infinitum to spell out every situational, material and (heaven help us all) psychological detail of Jesus's earthly existence only serves to obscure his identity.

Of course, you know what they say about the details... and these divinely instructed biographers just can’t seem to get them right. Cora Evans expounds an upside-down ahistorical crazy world, which we won’t even get into. Bear in mind, Mrs. Evans believed herself to have been physically teleported through time and space to the Holy Land of the First Century, and thus to be reporting “an eyewitness account.” Valtorta characterized her work as “the Gospel as Revealed to Me.” I looked up the passage quoted at the beginning of this post, because Sandra Miesel mentions that Valtorta’s Christ is situated in climes which are unrelentingly European. Apple orchards predominate the landscape. The text I blocked happened to overrun and include several extra sentences:

By far more powerful than your electric current, My Spirit entered like a sword of divine Fire to warm the cold remains of My Corpse, and in the new Adam the Spirit of God breathed life, saying to Itself: “Live. I want it.” I, Who had raised the dead when I was only the Son of Man, the Victim appointed to be burdened with the sins of the world, should I not have been able to raise Myself, now that I was the Son of God, the First and the Last, the eternal Living Being, He Who holds in His hands the keys of Life and of Death?

Oh… my… goodness. That is some kind of theology. The metaphysician in me is getting twitches, just pasting it into this post. We’ve got multiple problems going, and that’s bypassing any analysis of the text; when I was only the Son of Man obviates wasting words on anything more subtle or elaborate (but because I can’t resist the bait, assuming that Christ as newly divinized is the principle of the action, why is he being sent by the Holy Spirit? Contrast this to the ancient homily for Holy Saturday, in which Christ, even in Hell, restores to man “that first divine inbreathing at creation.”).

There are errors foundational to the whole genre. The mechanism by which extraordinary graces occur is not understood in line with mystical theology. Distinctions between categories of revelation are not appropriately maintained. Theology is not respected – as Merton warns in another of his works, “beware of contemplatives whose mysticism does not have a positive basis in theology” – and where it is, it receives insufficient philosophical formation, so that it is not properly understood. We will be examining all of these difficulties in future posts.

But there are deeper issues still. First, the hyperemphasis on discursive “realism” (however strange a vision of reality it betrays) sets everything on the wrong track and is spiritually stifling. This works to the detriment of the intuitive, and of faith. All of this together warps the aesthetic sense. (This, too, will be treated of, in the time to come.) Moreover, Merton connects resistance to the symbolic to a crypto-manicheanism. He does not expound on that, but it seems clear enough that where being is divested of its metaphysical import, we may distinguish the good only by an artificially appended “religious” veneer. Not knowing how else to proceed, the carnal mind will interpret that imputed religious character as a sort of wholly earthbound magic. (An aside which draws out the analogy: the phenomenon of “Christian pop”, carefully crafted to mimic its secular counterpart, is just such a “religious” facade; it tends to fail as art and prayer alike, while nonetheless lending itself quite well to commercialization.)

But let’s go deeper still; here, I will extrapolate from Lagrange. In the seventeenth century, for various historical reasons, a rift began to take place between ascetical and mystical theology, absolutizing their separation. Up to that point, mystical theology had included the general question of Christian perfection, which consists in charity, achieved through faith, the “normal progress of which seemed directed toward the mystical union as its culminating point,” whereas ascetical theology was taken as pertaining to action, particularly as directed to the cultivation of virtue. After that point, ascetical theology absorbed the essential content of mystical theology – the purgative, illuminative and unitive ways. This was thought to apply to “ordinary” Christians. Mystical theology then became the province of the extraordinary, pertaining only to unusual phenomena and rare souls. Adherence to this model flies in the face of the loftiest aims of the Vatican II reforms. Unpacking this is beyond my current scope, although introducing it is important – or actually, urgent.

Now we see, at least a bit more, something of our bias. Ancient myth sought to explain the world as much as to tame its deleterious forces; in the modern era, practical knowledge is esteemed preferable to speculative. Remember the move, occurring around the same time as the circumscription of mystical theology, from equating being and truth (verum est ens) to seeing truth as following on our own works (verum quia factum). We as moderns can only know the work of our hands – or, if you will, what is discursively accessible to the mind. This establishes a low-ceilinged humanism which gives primacy to the historical over the existential.

Unwittingly, we have doubly dragged heaven down to earth, philosophically and theologically, truncating it to fit our own existential dimensions. What is truest in religion has always done the opposite. Whereas an icon is effective insofar as representational realism is eschewed in preference to a disciplined “fasting of sight,” literalism suffocates the soaring genius of the creation account in Genesis, of the poetry of Job, of the sublimity of the Christological titles found in the O Antiphons, of the astounding imagistic marvel and depth psychology in the Book of Revelation, and offers instead something more akin to religious reality television, with a monotonous banality that doesn't really go anywhere.

The soul is distinguished as rational by its capacity to think in universals; divesting sensory apprehension of particulars is the laborious task of the agent intellect, which is emphatically not the domain of contemplation. A hunger for endless particular knowledge as food and sustenance is something like spiritual pica. These accounts posing as Gospel truth, simply by virtue of being independent works, are dislodged from the integrality of Scripture. This alone colors their interpretation, while a fundamentalist-type attachment to literalism precludes in advance any allegorical or anagogical connotations of the narratives being presented, even were such to be had.

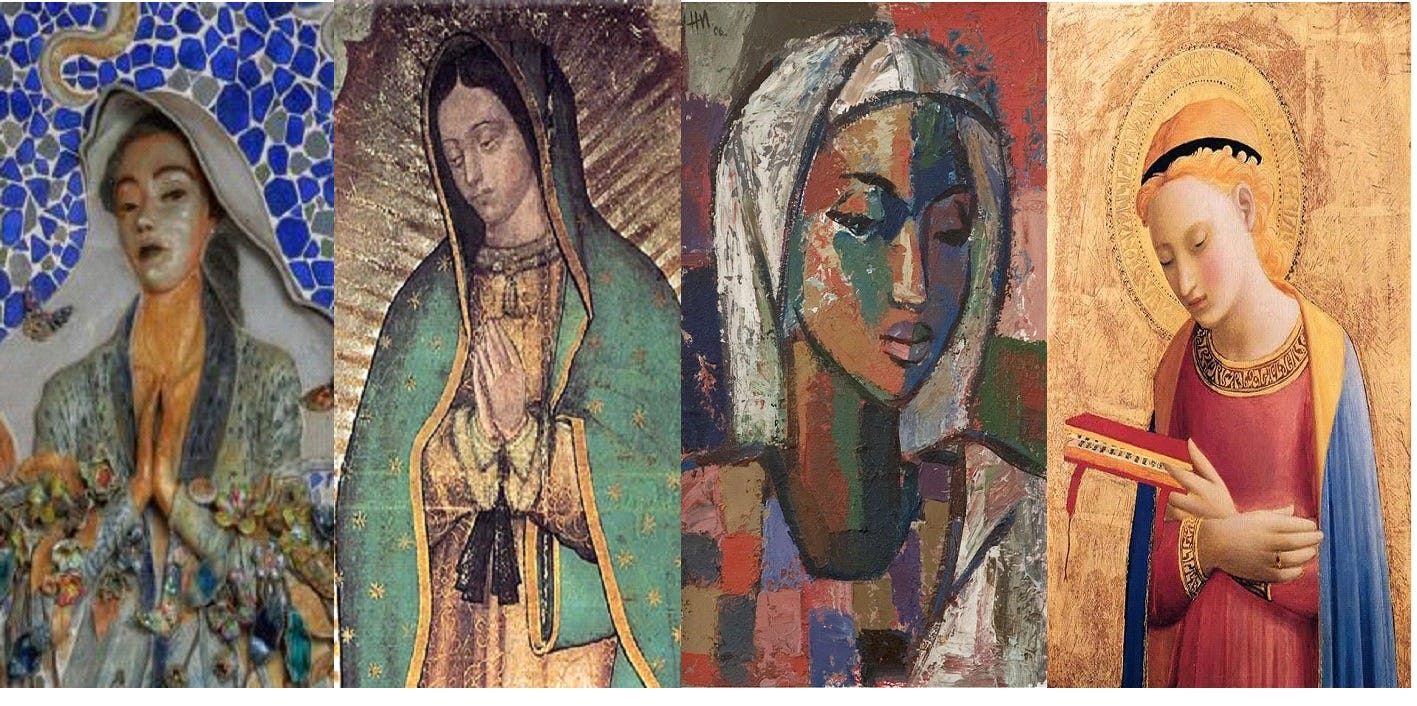

Also, where the circumstances of the life of Christ are apodictically misidentified with one’s own experiences, insularisms arise. Valtorta’s work, for example, is notoriously antisemitic. Cora Evans, with her 1950’s American sensibilities, portrays a Christ who does not nurse, [i] but is allowed to be bottle-fed cow’s milk as a ruse to preserve the messianic secret (for her, Jesus in his humanity had no need of food). In contrast, archetypal thinking encourages a catholicity whereby a re-imaging of oneself and one’s particular beauty can occur, seamlessly and gloriously, according to a mutually informing interculturality – witness the harmony of Semitic and Aztec elements in the Guadalupe image.

Pieper reminds us of a little-known principle in Aquinas, drawn from his Commentary on Aristotle's Metaphysics: the concern of poetry and philosophy is the mirandum, the “wonderful”. This wonderful relates, not to any prodigy, but to wisdom – which, as Aquinas himself tells us in the Summa, perfects the speculative intellect for its consideration of highest causes.

Much more to come in this series!

[i] For a beautifully written article which touches on the authentic tradition of the Blessed Virgin nursing the Holy Infant, see Michael Centore, "'Africa & Byzantium' show traces sacred histories of Christian antiquity", National Catholic Reporter, March 2, 2024.