But of that day and hour no one knows, neither the angels of heaven, nor the Son, but the Father alone.

A week or two ago, I received an email with a question from someone I deeply respect, a long-time student of Roger Duncan and a colleague in the Balthasar study circle he founded and led. The group has been working with the topic of substance rather intensively for some months, and especially on certain inadequacies in the concept as it stands. Moreover, Trinitarian theology and interpersonal relation are perennial concerns for the group. In that context of thought, and in view of these last hours of the liturgical year, an issue arises naturally, as follows:

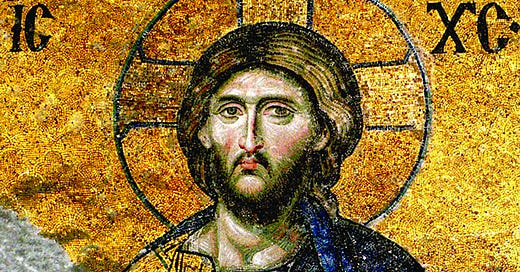

Christ and the Father are in no way circumscribed, each in his own delineated purlieu of being; they are absolutely not substances walled off in self-enclosure, but are rather one in being, each defined as person precisely in and through the self-giving act of relationality. Indeed, Jesus declared of himself, at immediate peril of stoning, no less: "The Father and I are one." (John 10, 30) Given all this, how are we to understand the Gospel of Matthew proclaimed at Mass for the penultimate Sunday of the year, regarding the ultimate day of the world: “But of that day and hour no one knows, neither the angels of heaven, nor the Son, but the Father alone"?

It's a really good question. Jesus's self-imputed ignorance on the matter was something of a scandal to Christian piety, as witnessed by the omission of the phrase "nor the Son" in some early manuscripts. St. Jerome was troubled by the concession to Arius an unsophisticated reading would yield; the Son, lesser in the order of knowledge, would then exist as ontically subordinate and not as co-equal.

I, of course, do not know the answer. The Fathers were not exactly of one mind in the interpretation of Matt. 24:36. Catechetical, and even theological, definitions and formulae, however hard-won and necessary, orient us to the domain of mystery, opening us out to contemplation's broader horizon. Looking to this question may afford us salutary matter for meditation for this last day of the liturgical calendar, even absent a totally definitive answer.

In Eschatology, Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger looks to Jean Daniélou in sorting out how Christ's coming and the temporal order of the human experience are related, one to another. The Scriptures themselves support opposing approaches. On the one hand, the seeking of "signs" is staunchly discouraged as inappropriate. Christ's coming is too discrepant with historical time for history to have any say in its discernment: "In so calculating, man works with history's inner logic, and thereby misses Christ, who is not the product of evolution or a dialectical stage in the processive self-expression of reason..." This is all true. Certainly, according to his human nature, Christ could stand in unique solidarity with humankind's angst regarding the specifics of its fate, yet insofar as Christ's divine and human natures are incorporated into a single personhood, this answer fails to be completely gratifying.

On the other hand, Jesus himself advises that, of his coming, there are signs; for instance:

Immediately after the tribulation of those days, the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will fall from the sky, and the powers of the heavens will be shaken.

Here again, following Daniélou, Christ's humanity is to be taken into account; in his acting as man, the temporal process is the necessary medium of such action. Christ is history's telos, yet its peras, or boundary, as well. He is history's fulfillment, preconditioned on the facts that man is a) powerless in and of himself to achieve his own redemption from the constraints of historical time, and b) implicated and affected directly by that fulfillment, to the degree of total and inextricable involvement.

Let us take a brief digression to consider the apocalyptic figure of Jesus's antitype in historical culmination, the Antichrist, insofar as doing so will shed paradoxical light on the question at hand. St. Paul, in developing his own eschatology, has recourse to the tradition of the Old Testament. The prophets Daniel and Ezekiel each condemn as archnemesis a known historical personage: Antiochus Epiphanes and the Prince of Tyre, respectively. The character of the Antichrist is therefore not unknown to the past, nor is it to be taken in any way as superlatively novel. Similarly, St. John the Evangelist, through the image of the two beasts, identifies the Antichrist with the Roman state. The Antichrist is no innovator, nor some seductively hip creative of a fast-expiring timeline; no, it is, rather, same old, same old – in the case of Johannine literature, the decidedly unglamorous, numbing monolith of mindless, self-perpetuating institution absent telos. If we consider that the Antichrist shapeshifts to the contours of each era so as to try all peoples, we can trace a fundamental "dechronologizing" of the Antichrist, and with it of eschatological signs themselves.

The "End" thereby ceases to be something concretely calculable, as with the Mayan calendar that was so the rage in 2012. Yet by the same token, unanticipated travail will overtake those complacent in their imagined peace and security – those marrying and given in marriage, eating, drinking, buying, selling, planting and building. Perhaps in doing these things as if they had no other, more transcendent occupation, they make themselves insensible to Christ present in his poor, blind to him in our midst. For as Ratzinger writes, "[T]he time of the End is ever present, for the world never ceases to touch that 'wholly Other' which, on one occasion, will also put an end to the world as chronos."

It is interesting to note that Ratzinger understands in Paul's reference to the conversion of the Jews in his Letter to the Romans no actual empirical event. Even St. Paul himself did not count it among the signs he enumerates.

The response to Christ's coming can only be "watchfulness." Tense and calculating self-involvement is the very antithesis of anticipation of a Beloved. Light and darkness have been set before us. Because we are temporal, we are projected into the future, and it matters whether we believe that future to be one of eschaton or of entropy; because we are spiritual, hope is constitutive of who we are. The irrational cyclic repetitions of a Nietzschean cosmos, like an old 33 with a skip, churn and go nowhere. Only with the engagement of another dimensionality, like lifting the needle from the uniplanar LP record, can liberation come.

In the ancient world, political power construed its scope as unlimited. Empire building flattered itself as reaching through the entirety of the cosmos. Even now, as we plant our flags on the moon (mind you, I love space travel... not that I've tried it personally, but you knew that already) and seek to "occupy Mars", we must acknowledge that each new frontier, no matter how distant, is but geographic, and alas, subject to history's decay. All the kingdoms offered in the Third Temptation are of interest now only to a few archeologists and historians; they are gone. Christ's kingship alone pertains to man's heart, to his soul, to his eternal destiny – realities which exceed, rightly, the power of the state even to confess. Only Christ's kingdom is truly universal, universal in a way which is comprehensive for its spirituality. As such, Christian eschatology's cosmic symbols (lifted from ancient secular usage, and illustrative of their inner transformation in Christ), are, at the same time, liturgical. Again Ratzinger: "The Parousia is the highest intensification and fulfillment of the Liturgy. And the Liturgy is Parousia, a Parousia-like event taking place in our midst."

Christ's Second Coming, like his Resurrection, is simultaneously fully historical and suprahistorical. It breaks into history from within and from above, ushering in, as Pope Benedict XVI writes in Jesus of Nazareth, "an ontological leap... one that touches being as such." Long before assuming the papacy, he wrote in Principles of Catholic Theology:

[T]he Resurrection cannot be a historical event in the same sense that the Crucifixion is. For that matter, there is no account that depicts it as such, nor is it circumscribed in time otherwise than by the eschatological expression "the third day."

Here we encounter a similar "dechronologizing," not on the erroneous basis of dislodging the facts of the life and death of the historical Jesus of Nazareth from the specificity of time and place, but in grateful awe before the mystery of divine action in our world. In Ratzinger's Eschatology, we read of Christ as "'the Other' who throws open the portals of time and death from the outside."

Turning to the Fathers and Doctors on Matthew 24:36, Aquinas offers a similar dechronologizing; just two verses earlier we find this text, with regard to the fulfillment of the calamities described in Jesus's discourse: "Amen, I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things have taken place" – and, for the Angelic Doctor, "all the faithful are one generation." Jerome and Augustine understand our Lord as indicating a deliberate withholding of information which he in fact knows. It is Origen who will not separate the historical, nor even the divine, Christ from his mystical body. Interestingly, Augustine adds, "the coming of the judgement cannot be known determinately."

All of this brings us to a fascinating twofold thesis: 1.) Christ's "knowing" of the day and the hour is necessarily incomplete until, by analogy, what is "lacking" is filled up in the flesh by the saints on behalf of his body, which is the church; 2.) The day and hour are "indeterminate" in the sense, not of a deficiency in divine foreknowledge (which is absurd) but as manifesting the relationship of God's ever-simultaneous creating of the world to man's finite though free co-creation thereof. The eschaton can be understood, “known,” not as pre-programmed terminus, but purely and wholly as consummation. It resists the dictatorship of clock-time every bit as much as does an apple ripening on a tree branch, i.e. the world is not a "product." God is not like Amazon; he must not be marred by our undue esteem for authority as expressed in the enforcement of arbitrary deadlines and schedules of efficient planning. He is patient.

Turning once more to Benedict, from his preaching of a Sunday Angelus in November of 2012:

...Jesus does not describe the end of the world and when he uses apocalyptic images, he does not act as a 'seer'. On the contrary, he wishes to prevent his disciples in every epoch from being curious about dates and predictions; he wants instead to provide them with a key to a profound, essential interpretation and, above all, to point out to them the right way on which to walk, today and in the future, to enter eternal life.

Such is the way of the gentle Pantocrator, the true King of the Universe, who is also the Good Shepherd, one with the Father, as we are told in John 10. No pitch of righteousness, no apex of human achievement, can precipitate the Day of the Lord. God responds to our utter failure, misery and incapacity to help ourselves, as inestimable sheer Mercy. To what Balthasar called "our ever-growing no," God offers his never-ending "Yes." On this final day of the calendar year, may we stand watchful, joining our voices as the Spirit and the Bride say, "Come!"

V.J.,

I enjoyed this meditation. It reminds me in certain respects of an article I wrote for HPR last year entitled "Advent and Eschaton" (https://www.hprweb.com/2023/11/advent-and-eschaton/).

I am mostly persuaded that the Olivet Discourse has its primary and immediate fulfillment in the judgment of Jerusalem, and especially the Temple, with all the salvation-historical implications of that event: namely, the definitive conclusion of the Mosaic dispensation, the universalization of the commonwealth of Israel, and the end of the angelic dominion of the nations, all of which have profound religious, social, political, and cosmic dimensions. Hence the Discourse represents one of the most powerful prophecies of the Lord, brought to completion within a generation, as He said. (Actually, I'm convinced that almost all of the prophecies uttered in the pages of Old and New Testament alike have already seen their primary and immediate fulfillment; count me as adjacent to the "orthodox preterists" on this count.) Of course, the Discourse has its secondary and remote fulfillment in the judgment of the world: words symbolize things, and things symbolize other things, a dynamic our Lord Himself affirms by repurposing Daniel's prophecy, which was initially fulfilled in Antiochus Epiphanes and his sacrilege, as you note.

As for the Lord's profession of ignorance connected therewith, I am convinced by the exegesis of St. Basil (among other fathers), who says in Epistle 236 that the Son indicates the principality of the Father: that is, so sublime is the mystery of the times and the dispensations of God that knowledge of the same must be ascribed especially to the Father, who is the wellspring of reality, the principle even of the Son. That Christ expresses this principality in the servant's form is doubly telling, and gestures toward the mystery of his condescension and the enigmatic position of man in time.

I believe that a number of theological puzzles, and especially hermeneutic difficulties, can be resolved by moving away from a naive account of time, which is our default account, as Augustine skillfully demonstrates in Book 11 of The Confessions (also, a naive account of space, but that is a theme for another post). To use a frequently-encountered example, no one can really tell me what a day is, nor explain my relative experience thereof, but everyone is quick to opine as to the meaning of the six days of creation, and to assert what is absurd or commonsensical about this or that interpretation.

Moreover, given the irruption of eternity into time with the incarnation, and particularly the resurrection, and the consequent diffusion of the heavenly kingdom and the new creation in the midst of the present evil age, the Christian cannot cling to a stark distinction of chronos and eschatos. At least, no Christian who has any understanding of the liturgy . . .

Of course, this truth, like all others, can be taken to extremes: hence ill-advised attempts to totally displace the fruition of the paschal mystery from the realm of space-time (as opposed to situating it on the frontier of the same, its juncture with eternity, a la Ratzinger), thus rendering the Lord's destiny utterly resistant to the normal means of historical study. I do want to avoid an exaggerated dechronologizing, which ends in idealism and contempt for time. The scandal of the particular has a temporal aspect, as well.

In any event, thank you for this thoughtful reflection, which I will continue to chew on. A blessed and most fruitful Advent to you.

In Christ,

Philip